Summary

Current Position: US Representative of NY District 7 since 1993

Affiliation: Democrat

Candidate: 2021 US Senator

Former Position: New York City Council from 1993 – 2013

Other Positions: Chair, House Small Business Committee

District: Includes parts of Brooklyn and Queens

Velázquez chaired the Congressional Hispanic Caucus until January 3, 2011. Her district, in New York City, was numbered the 12th district from 1993 to 2013 and has been numbered the 7th district since 2013. Velázquez is the first Puerto Rican woman to serve in the United States Congress.

OnAir Post: Nydia Velázquez NY-07

About

Source: Government page

Congresswoman Nydia M. Velázquez is currently serving her fourteenth term as Representative for New York’s 7th Congressional District. In the 116th Congress, she is the Chairwoman of the House Small Business Committee, a senior member of the Financial Services Committee and a member of the House Committee on Natural Resources.

Congresswoman Nydia M. Velázquez is currently serving her fourteenth term as Representative for New York’s 7th Congressional District. In the 116th Congress, she is the Chairwoman of the House Small Business Committee, a senior member of the Financial Services Committee and a member of the House Committee on Natural Resources.

She has made history several times during her tenure in Congress. In 1992, she was the first Puerto Rican woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. In February 1998, she was named Ranking Democratic Member of the House Small Business Committee, making her the first Hispanic woman to serve as Ranking Member of a full House committee. Most recently, in 2006, she was named Chairwoman of the House Small Business Committee, making her the first Latina to chair a full Congressional committee.

Given these achievements, her roots are humble. She was born in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico – a small town of sugar-cane fields – in 1953, and was one of nine children. Velázquez started school early, skipped several grades, and became the first person in her family to receive a college diploma. At the age of 16, she entered the University of Puerto Rico in Rio Piedras. She graduated magna cum laude in 1974 with a degree in political science. After earning a master’s degree on scholarship from N.Y.U., Velázquez taught Puerto Rican studies at CUNY’s Hunter College in 1981.

But her passion for politics soon took hold. In 1983, Velázquez was appointed Special Assistant to Congressman Edolphus Towns (D-Brooklyn). One year later, she became the first Latina appointed to serve on the New York City Council.

By 1986, Velázquez served as the Director of the Department of Puerto Rican Community Affairs in the United States. During that time, she initiated one of the most successful Latino empowerment programs in the nation’s history – “Atrevete” (Dare to Go for It!).

In 1992, after months of running a grassroots political campaign, Velázquez was elected to the House of Representatives to represent New York’s 7th District. Her district, which encompasses parts of Brooklyn, Queens and the Lower East Side of Manhattan, is the only tri-borough district in the New York City congressional delegation. Encompassing many diverse neighborhoods, it is home to a large Latino population, Jewish communities, and parts of Chinatown.

As a fighter for equal rights of the underrepresented and a proponent of economic opportunity for the working class and poor, Congresswoman Velázquez combines sensibility and compassion, as she works to encourage economic development, protect community health and the environment, combat crime and worker abuses, and secure access to affordable housing, quality education and health care for all New York City families.

As the top Democrat on the House Small Business Committee, which oversees federal programs and contracts totaling $200 billion annually, Congresswoman Velázquez has been a vocal advocate of American small business and entrepreneurship. She has established numerous small business legislative priorities, encompassing the areas of tax, regulations, access to capital, federal contracting opportunities, trade, technology, health care and pension reform, among others. Congresswoman Velázquez was named as the inaugural “Woman of the Year” by Hispanic Business Magazine in recognition of her national influence in both the political and business sectors and for her longtime support of minority enterprise.

Although her work on the Small Business Committee and the House Financial Services Committee (where she is the most senior New York Member on the Subcommittee on Housing and Community Opportunity) keeps her busy, Congresswoman Velázquez can often be found close to home, working for the residents of her district.

Personal

Full Name: Nydia M. Velázquez

Gender: Female

Birth Date: 03/22/1953

Birth Place: Yabucoa, Puerto Rico

Home City: Brooklyn, NY

Religion: Roman Catholic

Source: Vote Smart

Education

MA, Political Science, New York University, 1976

BA, Political Science, University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, 1974

Political Experience

Candidate, United States House of Representatives, New York, District 7, 2022

Representative, United States House of Representatives, New York, District 7, 2013-Present

Representative, United States House of Representatives, New York, District 12, 1993-2013

Council Member, New York City Council, 1984-1986

Offices

Washington, DC Office

2302 Rayburn House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

Brooklyn Office

266 Broadway

Suite 201

Brooklyn, NY 11211

Lower East Side Office

500 Pearl Street

Suite 973

New York, NY 10007

Contact

Email: Government

Web Links

- Government Site

- Campaign Site

- Congress.Gov

- Google Search

- Wikipedia

- YouTube

- Ballotpedia

- Open Secrets

Politics

Source: none

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

Committees

Congresswoman Velázquez is the Chairwoman of the House Small Business Committee.

She is a member of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus.

The Congresswoman is also a senior member of the Financial Services Committee and serves on the following Subcommittees:

- Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit

- Subcommittee on Housing and Insurance

The Congresswoman is also a member of the House Committee on Natural Resources and serves on the following Subcommittees:

- Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources

- Subcommittee on Indian, Insular and Alaska Native Affairs

In addition, she serves on the following Congressional Caucuses and Task Forces:

- Congressional Progressive Caucus

- Congressional Asian American Pacific Caucus

- Democratic Caucus

- Women’s Issues Caucus

- Urban Caucus

New Legislation

Learn more about legislation sponsored and co-sponsored by Congresswoman Velazquez.

Issues

Source: Government page

Congresswoman Velázquez believes a cleaner environment means working people will have healthier communities in which to raise their families.

Today, there is a shamefully large gap between the rich and the poor in America. Working families should not have to live in poverty in a country of our wealth.

It is unacceptable that the United States of America is the only developed country in the world that does not have a universal healthcare system for its citizens.

Congresswoman Velázquez is dedicated to ensuring that New York City residents have housing options that are both affordable and accessible.

Small firms are the backbone of the American economy, and nowhere is that more clear than in New York City.

More Information

Services

Source: Government page

View types of services our office provides, and how to request more information or other assistance. Please contact us if you need help with a federal agency, would like to order a flag, are requesting tours and tickets for a visit to Washington, DC, or are considering applying to a military academy.

Every year, the United States Congress considers the need to fund specific federal government departments, agencies and programs.

District

Source: Wikipedia

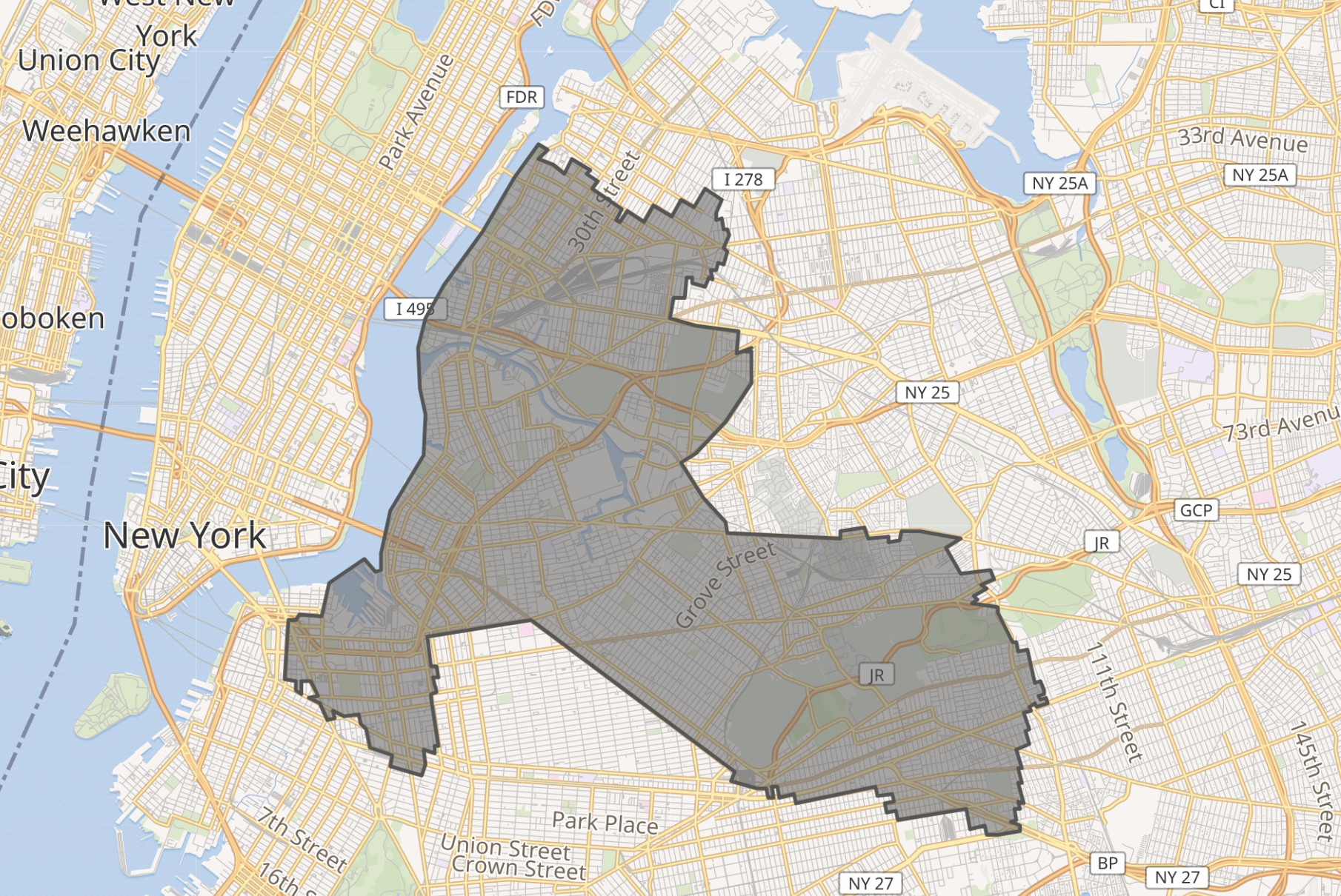

New York’s 7th congressional district is a congressional district for the United States House of Representatives in New York City. It includes parts of Brooklyn and Queens. Democrat Nydia Velázquez represents the district in Congress.

New York’s 7th congressional district is a congressional district for the United States House of Representatives in New York City. It includes parts of Brooklyn and Queens. Democrat Nydia Velázquez represents the district in Congress.

Like many Congressional districts around the country, the New York Seventh’s boundaries were drawn as to link disparate and widely separated neighborhoods with a large percentage of minority voters (see majority-minority districts). While no minority in the district constitutes an absolute majority, the boundaries group together heavily Puerto Rican neighborhoods in the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens.

The district includes the Queens neighborhoods of Long Island City, Astoria, Sunnyside, Maspeth, Ridgewood, and Woodhaven; the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bushwick, Clinton Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, East New York, East Williamsburg, Fort Greene, Greenpoint, and Williamsburg.

Until 2012, the 7th consisted of parts of Northern Queens and Eastern portions of the Bronx. The Queens portion included the neighborhoods of College Point, East Elmhurst, Jackson Heights and Woodside. The Bronx portion of the district included the neighborhoods of Co-op City, Morris Park, Parkchester, Pelham Bay, and Throgs Neck as well as City Island. Until the latest redistricting in 2022, the 7th also included a portion of Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

Wikipedia

Contents

Nydia Margarita Velázquez Serrano (/ˈnɪdiə/ NID-ee-ə, Spanish: [ˈniðja βeˈlaskes]; born March 28, 1953) is an American politician serving in the United States House of Representatives since 1993. A Democrat from New York, Velázquez chaired the Congressional Hispanic Caucus until January 3, 2011. Her district, in New York City, was numbered the 12th district from 1993 to 2013 and has been numbered the 7th district since 2013. Velázquez is the first Puerto Rican woman to serve in the United States Congress.[1]

Early life, education and career

Velázquez was born in the town of Limones in the municipality of Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, on March 28, 1953.[2] She grew up in Yabucoa[3] in a small house on the Río Limones.[1][4] Her father, Benito Velázquez Rodríguez, was a poor worker in the sugarcane fields who became a self-taught political activist and the founder of a local political party; he was also listed as Black (“de color”) on the census.[1][5] Political conversations at the Velázquez dinner table focused on workers’ rights. Her mother was Carmen Luisa Serrano Medina.[1] She was one of nine siblings.[1]

Velázquez attended public schools[2] and skipped three grades as a child.[1] She became the first in her family to graduate from high school.[2][4] She became a student at University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras at age 16.[1] In 1974,[2] she received a B.A. degree in political science, magna cum laude, and became a teacher.[1][4] In college, Velázquez supported Puerto Rican independence; by the time she ran for Congress in 1992, Velázquez no longer addressed the issue, saying that it must be left up to the Puerto Rican people.[1]

In 1976, Velázquez received an M.A. degree in political science from New York University.[2] She served as an instructor of political science at the University of Puerto Rico at Humacao from 1976 to 1981.[2] After returning to New York City, Velázquez was an adjunct professor of Puerto Rican studies at Hunter College from 1981 to 1983.[2][1]

Political career

In 1983, Velázquez was special assistant to Representative Edolphus Towns, a Democrat representing New York’s 10th congressional district in Brooklyn.[2][1]

In 1984, Howard Golden (then the Brooklyn Borough president and chairman of the Brooklyn Democratic Party)[6] named Velázquez to fill a vacant seat on the New York City Council, making her the first Hispanic woman to serve on the council.[2][1] Velázquez ran for election to the council in 1986, but lost to a challenger.[1]

From May 1986 to July 1989, Velázquez was national director of the Puerto Rico Department of Labor and Human Resources‘ Migration Division Office.[2] In 1989 the governor of Puerto Rico named her the director of the Department of Puerto Rican Community Affairs in the United States.[2][1] In this role, according to a 1992 The New York Times profile, “Velazquez solidified her reputation that night as a street-smart and politically savvy woman who understood the value of solidarity and loyalty to other politicians, community leaders and organized labor.”[4]

Velázquez pioneered Atrévete Con Tu Voto, a program that aims to politically empower Latinos in the United States through voter registration and other projects. The Atrévete project spread from New York to Hartford, Connecticut; New Jersey; Chicago; and Boston, helping Hispanic candidates secure electoral wins.[7]

Puerto Rico

Velázquez has been an advocate for human and civil rights of the Puerto Rican people. In the late 1990s and the 2000s, she was a leader in the Vieques movement, which sought to stop the United States military from using the inhabited island as a bomb testing ground. In May 2000, Velázquez was one of nearly 200 people arrested (including fellow Representative Luis Gutiérrez) for refusing to leave the natural habitat the US military wished to continue using as a bombing range.[8] Velázquez was ultimately successful: in May 2003, the Atlantic Fleet Weapons Training Facility on Vieques Island was closed, and in May 2004, the U.S. Navy’s last remaining base on Puerto Rico, the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station – which employed 1,000 local contractors and contributed $300 million to the local economy – was closed.[9][10]

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

1992

Velázquez ran for Congress in the 1992 election, seeking a seat in the New York’s newly drawn 12th congressional district, which was drawn as a majority-Hispanic district.[4] She won the Democratic primary, defeating nine-term incumbent Stephen J. Solarz and four Hispanic candidates.[3]

2010

Velázquez’s 2010 campaign income was $759,359. She came out of this campaign about $7,736 in debt. Her top contributors included Goldman Sachs, the American Bankers Association, the National Roofing Contractors Association and the National Telephone Cooperative Association.[11]

2012

Velázquez, who was redistricted into the 7th congressional district, defeated her challengers to win the Democratic nomination.[12] Her top contributors included Goldman Sachs, the American Bankers Association and the Independent Community Bankers of America.[13]

Tenure

On September 29, 2008, Velázquez voted for the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. On November 19, 2008, she was elected by her peers in the Congressional Hispanic Caucus to lead the group in the 111th Congress.[2]

Before removing her name from consideration, she was considered a possible candidate to be appointed to the United States Senate by Governor David Paterson after Senator Hillary Clinton resigned to become secretary of state.[14]

Among Velázquez’s firsts are: the first Hispanic woman to serve on the New York City Council; the first Puerto Rican woman to serve in Congress; and the first woman Ranking Democratic Member of the House Small Business Committee in 1998. She became the first woman to chair the United States House Committee on Small Business in January 2007 as well as the first Hispanic woman to chair a House standing committee.[2]

Valazquez voted with President Joe Biden‘s stated position 100% of the time in the 117th Congress, according to a FiveThirtyEight analysis.[15]

Velázquez was among the 46 Democrats who voted against final passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 in the House.[16]

Committee assignments

- Committee on Financial Services[17]

- Committee on Small Business (chair)[19]

- Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis[20]

Caucus memberships

- Congressional Hispanic Caucus[21]

- Congressional Progressive Caucus[22]

- Women’s Issues Caucus[23]

- Urban Caucus[24]

- House Baltic Caucus[25]

- Congressional Arts Caucus[26]

- Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus[27]

- Climate Solutions Caucus[28]

- Medicare for All Caucus

- Blue Collar Caucus

Velázquez was formerly a member of the Congressional Out of Iraq Caucus.[29]

Personal life

Velázquez, also known as “la luchadora”,[30] married Brooklyn-based printer Paul Bader in 2000.[31] It was her second marriage.[31] In November 2002, New York City Comptroller Bill Thompson controversially hired Bader as an administrative manager in the Bureau of Law and Adjudications, joining Joyce Miller, wife of Representative Jerry Nadler, and Chirlane McCray, wife of City Councilman Bill de Blasio.[32] In 2010, Velázquez and Bader were in the process of divorce.[33]

In October 1992, during her first campaign for the House, an unknown person at Saint Clare’s Hospital in Manhattan anonymously faxed to the press Velázquez’s hospital records pertaining to a suicide attempt in 1991.[34] At a subsequent press conference, Velázquez acknowledged that she had attempted suicide that year while suffering from clinical depression.[34] She said that she underwent counseling and “emerged stronger and more committed to public service.”[34] She expressed outrage at the leak of personal health records and asked the Manhattan district attorney and the state attorney general to investigate.[34] Velázquez sued the hospital in 1994, alleging that the hospital had failed to protect her privacy.[35] The lawsuit was settled in 1997.[36][37]

See also

- List of Puerto Ricans

- History of women in Puerto Rico

- List of Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States Congress

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Newman, Maria (September 27, 1992). “From Puerto Rico to Congress, a Determined Path”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m “Hispanic Americans in Congress — Velázquez”. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Deborah Sontag, Puerto Rican-Born Favorite Treated Like Outsider, New York Times (November 2, 1992).

- ^ a b c d e Mary B. W. Tabor, The 1992 Campaign: 12th District Woman in the News; Loyalty and Labor; Nydia M. Velazquez, New York Times (September 17, 1992).

- ^ “Benito Velázquez Y Rodríguez in the 1940 Census | Ancestry”. www.ancestry.com. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ Frank Lynn, Democrats in Brooklyn Face Hispanic Demand, New York Times (August 16, 1984).

- ^ Carol Hardy-Fanta, with Jaime Rodríguez, Latino Voter Registration Efforts in Massachusetts: Un Pasito Más” in Latino Politics in Massachusetts: Struggles, Strategies, and Prospects (eds: Carol Hardy-Fanta & Jeffrey N. Gerson: Routledge, 2002), pp. 253-54.

- ^ Morales, Ed (May 11, 2000). “The Battle of Vieques”. The Nation.

- ^ New York Times: “After Closing of Navy Base, Hard Times in Puerto Rico” April 3, 2005

- ^ Los Angeles Times: “Navy Makes Plans Without Vieques – Use of bombing ranges in Florida and other U.S. mainland areas will increase after Puerto Rican island training ground is abandoned” January 12, 2003 Admiral Robert J. Natter, commander of the Atlantic Fleet, is on record as saying: “Without Vieques there is no way I need the Navy facilities at Roosevelt Roads — none. It’s a drain on Defense Department and taxpayer dollars.”

- ^ “Representative Nydia M. Velázquez”. Vote Smart. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- ^ “Rangel, Long, Meng, Jeffries, Velazquez Declared Winners In Primaries”. NY 1. June 26, 2012. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ “Rep. Nydia M. Velazquez – Campaign Finance Summary”. OpenSecrets.

- ^ Cadei, Emily (December 12, 2008). “New York Rep. Velázquez Out of Clinton Senate Seat Derby”. CQPolitics.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron; Wiederkehr, Anna (April 22, 2021). “Does Your Member Of Congress Vote With Or Against Biden?”. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Gans, Jared (May 31, 2023). “Republicans and Democrats who bucked party leaders by voting no”. The Hill. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ “Committee Members”. Financial Services Committee. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ “Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy”. Financial Services Committee. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ “Membership”. Small Business Committee. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ “Pelosi Names Select Members to Bipartisan House Select Committee on the Coronavirus Crisis”. Speaker Nancy Pelosi. April 29, 2020. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional Hispanic Caucus. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ “Caucus Members”. Congressional Progressive Caucus. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ “The Women’s Caucus”. Women’s Congressional Policy Institute. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ About Nydia Velázquez: Committees and Caucus Memberships

- Office of Nydia Velázquez (official website) (accessed April 10, 2016)

- ^ “Members”. House Baltic Caucus. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ “Membership”. Congressional Arts Caucus. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ “90 Current Climate Solutions Caucus Members”. Citizen’s Climate Lobby. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ Issues: Alternatives to War, Office of Nydia Velázquez (official website) (accessed April 10, 2016).

- ^ New York Times: “The Biggest Rival for a Congresswoman From Brooklyn Isn’t Even on the Ballot” by Sarah Wheaton June 20, 2012

- ^ a b Bob Liff, Rep. Velazquez to Marry Printer, New York Daily News (November 17, 2000).

- ^ New York Daily News: “Nydia’s Husband Gets Hired – He joins controller staff” by Celeste Katz November 22, 2002

- ^ Maite Junco, Dancing in the avenue: Q&A with Puerto Rican parade grand marshal Nydia Velázquez, New York Daily News (June 8, 2010).

- ^ a b c d Maria Newman, Candidate Faces Issue Of Suicide, New York Times (October 10, 1992).

- ^ Rep. Velazquez Sues St. Clare’s Hospital, New York Times (May 14, 1994). Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Cavinato, Joseph L. (2000), “YYYY”, Supply Chain and Transportation Dictionary, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 337–338, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4591-0_25, ISBN 978-1-4613-7074-1, retrieved October 3, 2021

- ^ Online court records for Nydia Velazquez v. St. Clare’s Hospital, Index No. 015736/1994, Kings County Supreme Court, accessible in the WebCivil Supreme section of New York’s eCourts website.

- ^ “Nydia Velázquez, Representative for New York – The Presidential Prayer Team”. November 27, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

External links

- Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez official U.S. House website

- Nydia Velázquez for Congress

- Nydia Velázquez at Curlie

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Appearances on C-SPAN